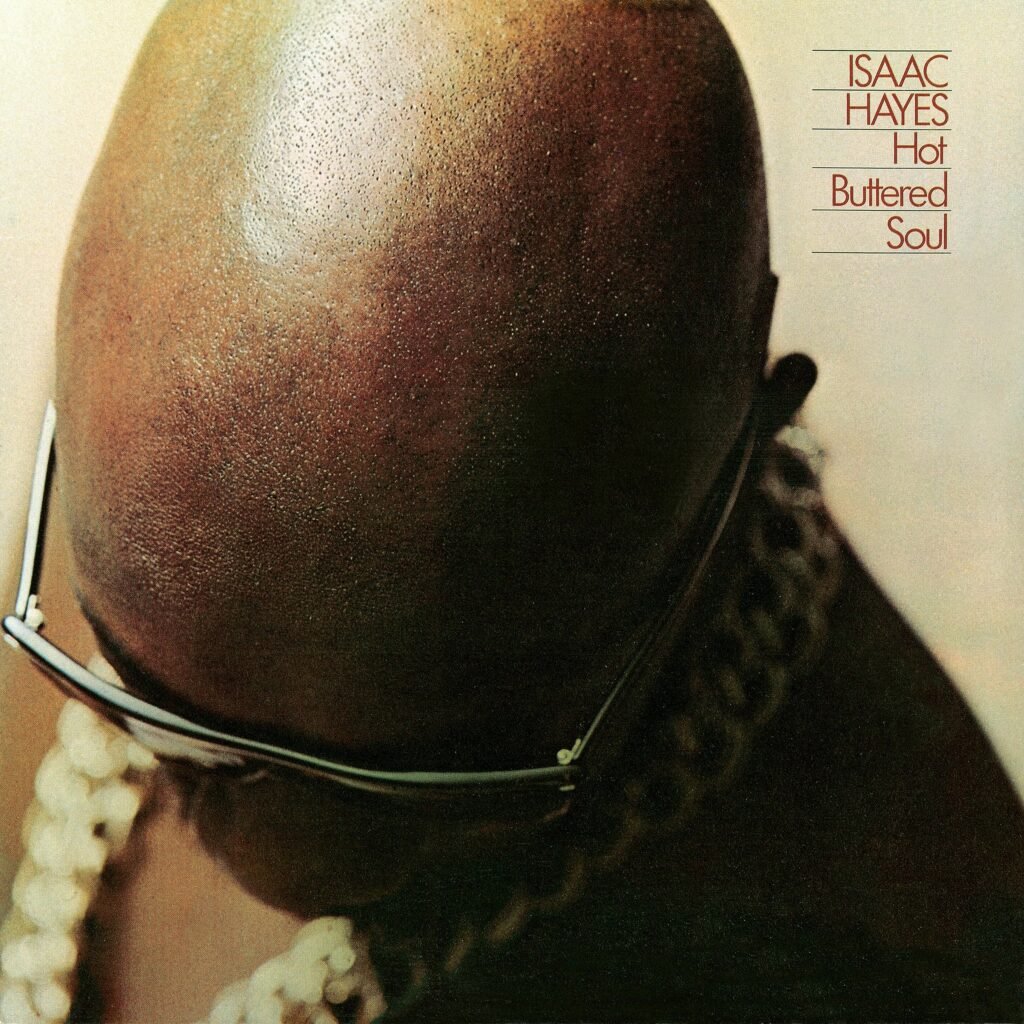

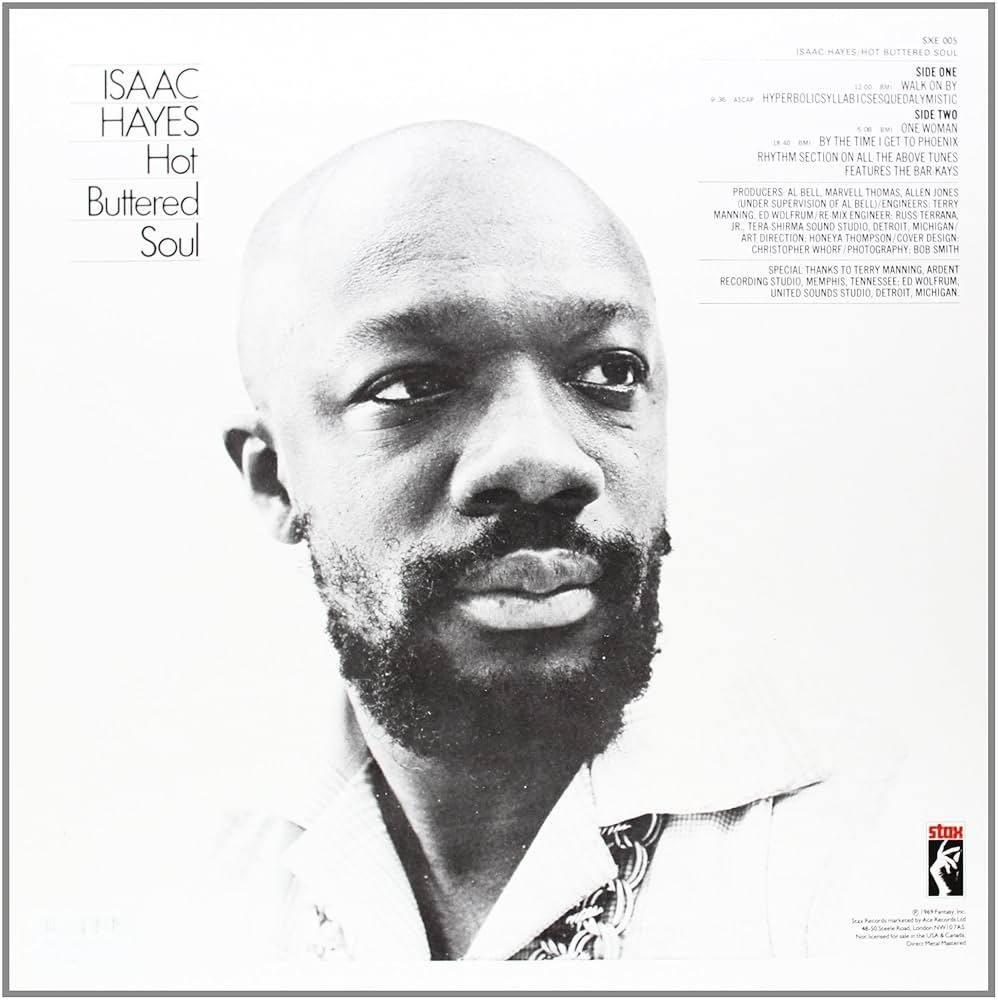

When Isaac Hayes walked into Stax’s Memphis studio in 1969, he wasn’t the star we think of today. He was a behind-the-scenes genius — a songwriter, producer, and session man whose fingerprints were already all over soul music, most famously as part of the Hayes-David Porter songwriting duo responsible for Sam & Dave’s “Soul Man” and “Hold On, I’m Comin’.” But the world outside Memphis didn’t really know his face yet.

Hot Buttered Soul changed that in one seismic stroke. Released in the aftermath of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination — which shook Stax and the entire Black community in Memphis to the core — the album was both a radical artistic statement and a subtle act of resistance. Hayes took the three-minute radio single format that dominated R&B and blew it up, stretching songs into sprawling, cinematic experiences. He fused gospel, jazz, orchestral pop, and deep funk into a new language of soul. In doing so, he not only redefined what Black popular music could sound like, but also gave voice to a broader cultural yearning for depth, dignity, and expansiveness in a moment when America was in flames.

What made Hot Buttered Soul such a gamble was the way it was made. After Stax lost its back catalog to Atlantic Records in a bitter split, the label needed fresh material fast, and Hayes — at the time still recovering from the commercial disappointment of his debut album — was given surprising freedom. He insisted on full creative control: the arrangements, the musicians, even the length of the tracks.

The sessions brought together some of Memphis’ finest, with Hayes leading the charge on vocals and keyboards. The Bar-Kays — who had tragically lost most of their members in the plane crash that killed Otis Redding two years earlier — stepped in as his rhythm section, lending the album its muscular but fluid backbone. Hayes also called in the Memphis Strings, bringing lush, cinematic orchestrations that draped themselves over the grooves like velvet curtains. The production was recorded at Ardent and Stax studios, with state-of-the-art equipment for the time, giving the record a depth and clarity that stood apart from rawer Southern soul records. Everything about the process was deliberate, ambitious, and defiantly against the grain of a singles-driven market.

The album only has four tracks, but each feels like a world in itself. It opens with “Walk On By,” a cover of the Burt Bacharach/Hal David tune made famous by Dionne Warwick. Hayes slows it down to a crawling tempo, stretches it past twelve minutes, and fills the spaces with wah-wah guitars, sweeping strings, and his trademark baritone, dripping with vulnerability and swagger. What was once a light pop lament becomes a psychedelic journey through heartbreak and desire.

Next comes “Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic” — and yes, that tongue-twisting title is deliberate. This is the funkiest cut on the record, a deep pocket jam where the Bar-Kays lock into a groove that could stretch forever. Hayes rides it with spoken-word bravado, half-sermon and half-pimp-talk, foreshadowing both Barry White’s seductive monologues and the entire rap tradition that would flourish a decade later. It’s not just a song, it’s a flex — Hayes proving he could be as raw and streetwise as he was lush and symphonic.

Flip the record, and you get “One Woman,” the most straightforward ballad here but no less powerful. Stripped back compared to the rest of the album, it’s a meditation on temptation and guilt, where Hayes’ voice hovers between confession and plea. The arrangement is tasteful, letting the emotional weight of the lyrics land without distraction. It’s the track that ties the album back to Southern soul’s church roots, grounding the experimentation in something universally relatable.

Then comes the closer, “By the Time I Get to Phoenix.” Jimmy Webb’s pop ballad had already been recorded by Glen Campbell and others, but Hayes transforms it into a 19-minute odyssey. He begins with a nearly nine-minute spoken prelude, essentially a short story about a man leaving his lover, delivered over a simmering groove. Only then does he slide into the actual song, turning Webb’s polished pop into a deep meditation on loss, regret, and escape. It’s equal parts theater, sermon, and late-night confessional, and it remains one of the boldest reinterpretations of a cover song in recorded history. By the time the record ends, you’ve been taken through an emotional journey that feels closer to cinema than a collection of songs.

Looking back, Hot Buttered Soul wasn’t just a hit album — it was a paradigm shift. It reached No. 8 on the Billboard 200, proving that expansive, uncompromising Black music could cross over without diluting itself. It paved the way for concept albums in soul and funk, setting the stage for Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, Curtis Mayfield’s Super Fly, and eventually the orchestral funk landscapes of Parliament-Funkadelic. Hip-hop producers from Public Enemy to DJ Quik have mined its grooves, and you can hear its DNA in everything from the quiet storm movement to neo-soul.

Half a century later, its relevance hasn’t faded. And if you need four reasons to spin it right now: first, it’s a masterclass in turning covers into revelations; second, it shows how Black music broke free of commercial constraints; third, it remains one of the smoothest yet most daring records to ever grace a turntable; and fourth, it’s pure proof that soul music, at its best, is as expansive and boundless as any symphony.

So next time you’re scrolling through playlists or digging through crates, don’t pass this one up — drop the needle, sink into the velvet grooves, and let Isaac Hayes remind you what hot buttered soul really feels like.