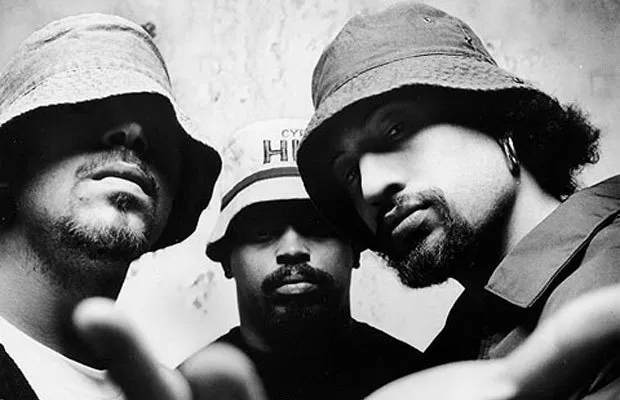

By the time Cypress Hill dropped Black Sunday in July 1993, the West Coast was already reshaping the rap game. Dr. Dre’s The Chronic had turned G-funk into a national phenomenon the year before, Snoop was about to drop Doggystyle, and gangsta rap was both vilified and unstoppable. But Cypress Hill were moving on a different frequency. They weren’t gangsta in the traditional sense, though their music had plenty of menace. They weren’t political like Public Enemy, though they carried a cultural weight. What they brought was something entirely their own: a hazy, bass-heavy, weed-soaked vision of hip-hop that centered Latino identity in a genre still largely dominated by Black voices, while also universalizing the stoner ethos. B-Real’s nasal, paranoid delivery, Sen Dog’s gruff counterpoints, and DJ Muggs’ sinister, psychedelic beats created a soundscape that was equal parts barrio, blunt session, and block party. Black Sunday wasn’t just an album — it was an atmosphere, one that resonated with hip-hop heads, suburban teens, and cannabis advocates alike, becoming a crossover moment that pushed hip-hop deeper into mainstream culture without losing its underground edge.

The making of Black Sunday was as meticulous as it was organic. DJ Muggs, the sonic architect, leaned heavily on obscure psychedelic rock, dusty soul, and funk samples, layering them with booming basslines and eerie organ riffs that felt like they were lifted from a B-movie soundtrack. Unlike many West Coast contemporaries who were drenched in Parliament-Funkadelic grooves, Cypress Hill’s production leaned darker, stranger, and more hypnotic.

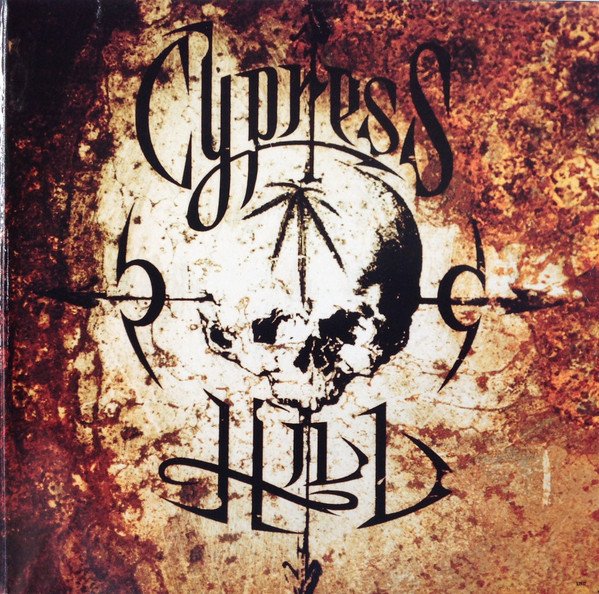

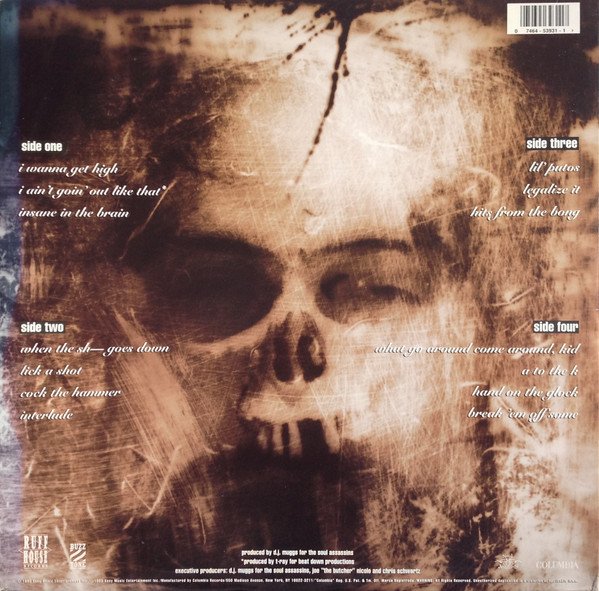

The album was recorded in Los Angeles, with Muggs at the helm and B-Real and Sen Dog shaping their verses in smoke-filled marathon sessions. There weren’t major guest features — Cypress Hill were their own ecosystem, their chemistry airtight. T-Ray, a rising producer at the time, contributed beats on “I Ain’t Goin’ Out Like That” and “Cock the Hammer,” adding grit to Muggs’ cinematic vibe. The sessions were loose but intentional: Cypress Hill understood they were building not just songs, but a mythology. Even the artwork — skulls, crosses, a gothic typeface — reinforced the idea that this was less a collection of tracks and more a ritual, an initiation into Cypress Hill’s world.

The album kicks off with “I Wanna Get High,” a two-minute invocation that sets the tone immediately. With its eerie organ loop and chant-like hook, it’s not just a weed anthem — it’s a declaration of intent, a mantra for the smoke circle. Then comes “I Ain’t Goin’ Out Like That,” a ferocious statement of defiance that earned them a Grammy nomination. Over T-Ray’s crushing guitar-driven beat, B-Real’s nasal bars cut sharp, while Sen Dog’s ad-libs hit like exclamation points. It’s a reminder that, despite their stoner reputation, Cypress Hill could come hard with raw aggression.

The third track, “Insane in the Brain,” is a runaway hit that became a cultural phenomenon. Built on a funky, bouncing Muggs beat with that unforgettable horn stab, the song turned B-Real’s nasal delivery into a global calling card. MTV ran the video on heavy rotation, suburban kids memorized the hook, and suddenly Cypress Hill were chart-topping stars. Yet, even as it went mainstream, the track never lost its grit — it was still strange, smoky, and undeniably theirs.

Side two of the album dives even deeper into their twisted soundscape. “Hits from the Bong” is the definitive stoner anthem, complete with a Dusty Springfield sample flipped into a woozy backdrop for B-Real’s ode to water pipes. It’s playful, iconic, and proof of Cypress Hill’s ability to turn weed culture into pop culture without watering it down. “When the Sh– Goes Down” is another standout, with its stripped-down groove and streetwise narrative — equal parts menace and humor, it’s the kind of track that reveals how Cypress Hill blurred the line between gangsta tales and stoner philosophy. “Cock the Hammer” keeps the intensity high, built on a menacing Muggs beat that feels like a soundtrack to a late-night alleyway. And while not every track hit radio, deep cuts like “Lick a Shot” and “What Go Around Come Around, Kid” showcase the consistency of the record — no filler, just layers of smoke and menace woven together. The sequencing matters: by the time the album winds down, you’re fully submerged in Cypress Hill’s world, head nodding, eyes low, lungs full.

Looking back, Black Sunday wasn’t just a hit album — it was a cultural shift. It debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200, selling over 260,000 copies in its first week, and went on to sell over 3 million in the U.S. alone. It made weed rap mainstream years before legalization was even on the political radar. It gave visibility to Latino voices in hip-hop, opening doors for artists from Kid Frost to Big Pun to Immortal Technique. It cemented DJ Muggs as one of the most innovative beatmakers of the era, influencing everyone from RZA to Alchemist. And it proved that hip-hop could be both uncompromisingly strange and massively popular. Thirty years later, it still knocks — the bass rattles, the organs haunt, the rhymes cut.

If you ask me for four reasons to listen the album right now, well: one, it’s the soundtrack that defined stoner rap; two, it’s a masterclass in eerie, sample-driven West Coast production; three, it’s a vital chapter in Latino hip-hop history; and four, it’s a record that turned weed smoke into a cultural movement. So, if you hace a record player, just drop the needle, light one up if that’s your vibe, and let Cypress Hill take you back to a Sunday that’s still blazing strong. Otherwise, fill the gap with your headphone and let the Cypress Hill’s smoked rhymes hit your soul.