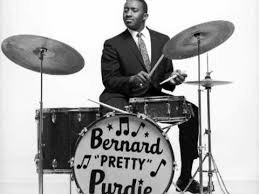

When you talk about drummers who shaped the very language of modern music, the name Bernard “Pretty” Purdie lands front and center. Born June 11, 1939, in Elkton, Maryland, Purdie grew up surrounded by rhythm. He built his chops on makeshift drum kits, hitting pots, pans, and whatever he could find until a neighbor passed along his first real set. The radio became his first conservatory—he soaked up big band swing, R&B shuffles, and gospel grooves, fusing the styles into a feel that was both fluid and sharp. Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Buddy Rich gave him a taste for swing; gospel drummers at church gave him that deep pocket. But what truly set him apart was his ability to make drums sing—to transform a rhythm into a voice of its own.

By the early 1960s, Purdie had moved to New York City, hustling in clubs and sessions, catching the attention of the right people with his speed, his stamina, and his uncanny ability to keep time like a human metronome. It wasn’t long before his name reached James Brown’s camp, and when the Godfather of Soul needed a drummer who could lock a groove so tight it squeezed oxygen out the room, Bernard Purdie stepped up. With Brown, he learned the art of precision funk, driving home the meaning of rhythm with the sharpness of a blade.

Purdie’s rise wasn’t about flash—it was about feel. His secret weapon was what he called the “Purdie Shuffle,” a ghost-note–laden half-time shuffle that married swing to funk. You hear it and instantly know you’re in the presence of groove royalty. That shuffle became his calling card, eventually showing up on tracks like Steely Dan’s Home at Last and Toto’s Rosanna (via Jeff Porcaro’s homage). But Purdie’s stardom wasn’t built on a single trick. It was his ability to adapt—laying down fatback funk for Aretha Franklin (Rock Steady), razor-sharp syncopations for James Brown, or rock-solid timekeeping for Hall & Oates. He wasn’t just keeping time; he was creating time, stretching and pulling the beat until it felt alive. Producers loved him because he could nail a first take. Musicians loved him because he made them sound better. Audiences loved him because every stroke of his sticks told a story. His impact spread across soul, funk, R&B, jazz, and rock, proving that a great drummer doesn’t just support a song—he defines it.

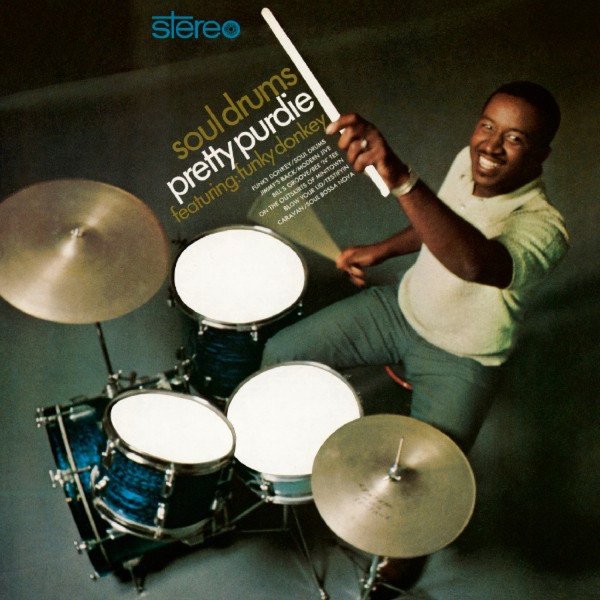

As Purdie’s reputation grew, so did his body of work. His solo career kicked off with Soul Drums (1967), an album that announced his arrival as a leader, not just a sideman. Through the seventies, he delivered projects like Purdie Good! (1971), Soul Is… Pretty Purdie (1972), and the soundtrack Lialeh (1973), each blending funk, soul, and jazz in ways that expanded what a drummer-led record could be. He became a first-call session musician, showing up on hundreds of records. The roll call of collaborators reads like a hall of fame: Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Nina Simone, B.B. King, Gil Scott-Heron, Steely Dan, Cat Stevens, Hall & Oates, Joe Cocker. With Franklin, he was the heartbeat behind some of her fiercest cuts. With Steely Dan, he was the studio wizard who could make impossibly precise grooves feel human. With Gil Scott-Heron, he anchored politically charged soul-jazz experiments. Purdie never limited himself—he played wherever the groove took him. And as decades passed, he kept recording, releasing teaching materials, and touring, always carrying the same message: rhythm is life.

Bernard “Pretty” Purdie isn’t just a drummer—he’s a movement. His grooves became templates for hip-hop producers, his shuffle a masterclass studied by generations, his session work the backbone of soul’s golden age. He taught us that the drums weren’t about showing off; they were about serving the song, deepening the emotion, and moving the body. Every ghost note he played whispered that less can be more, that nuance can be revolutionary. His fingerprints are all over Black music history, from soul’s church-born urgency to funk’s body-shaking syncopation. And today, his influence lives in every drummer who aims for pocket over pyrotechnics. Bernard Purdie showed that groove is eternal, and his legacy is proof that rhythm, when played with heart and precision, is as powerful as any lyric or melody. He remains, quite simply, the architect of groove.

Bernard Purdie Solo Discography

• Soul Drums (1967)

• Purdie Good! (1971)

• Soul Is… Pretty Purdie (1972)

• Stand By Me (Whatcha See Is Whatcha Get) (1971, Japan-only)

• Lialeh (Original Soundtrack) (1973)

• Purdie as Funky as He Wants to Be (1975)

• Delights of the Garden (with The Last Poets, 1978, often co-credited)

• Mr. Purdie (1978)

• Coolin’ ‘N Groovin’ (1993)

• Soul to Jazz (1997)

• Soul to Jazz II (1999)

• After Hours (2003)

Highlights of Collaborations

Bernard Purdie played on hundreds of records, but here are key highlights that showcase his impact:

• Aretha Franklin – Young, Gifted and Black (1972), Amazing Grace (1972), Rock Steady (single)

• James Brown – Various sessions, early ’60s live performances

• Steely Dan – Pretzel Logic (1974), The Royal Scam (1976), Aja (1977)

• Hall & Oates – Along the Red Ledge (1978)

• Nina Simone – Multiple sessions, including Silk & Soul (1967)

• B.B. King – King Size (1977)

• Cat Stevens – Catch Bull at Four (1972), Foreigner (1973)

• Gil Scott-Heron – Pieces of a Man (1971), Winter in America (1974)

• Joe Cocker – Stingray (1976)

Tomas Angel Jimenez

27 de January de 2026

Excelente artículo de este grande del jazz y la música !!