Born William Earl Collins in Cincinnati, Ohio, on October 26, 1951, Bootsy grew up in a city already pulsing with R&B, doo-wop, and the echoes of James Brown’s revolution. His mother, Lorean, encouraged his musical instincts, and by his early teens, Bootsy had swapped the guitar for the electric bass—the weapon that would forever etch his name into the book of funk. Together with his brother Phelps “Catfish” Collins on guitar, Bootsy formed The Pacemakers, a sharp local outfit that quickly built a reputation for fierce grooves.

The big break came in 1970 when the Collins brothers were drafted into James Brown’s band, joining The Godfather of Soul at the height of his creative power. Bootsy was barely 18. Within weeks, he found himself laying down bass lines on tracks like “Sex Machine” (1970) and “Super Bad” (1970), songs that defined the new funk era. That moment wasn’t just a career move—it was a baptism. From Brown, Bootsy learned discipline, the power of the “one,” and how funk wasn’t just a rhythm but a philosophy: keep it simple, keep it raw, keep it in the pocket. Those early years with James Brown gave Bootsy the foundation for everything that came after, a reminder that funk isn’t about how many notes you play—it’s about making people move.

By 1971, Bootsy and Catfish walked away from Brown’s strict regime, tired of the constant pressure and fines. Their exit opened the door to George Clinton, the psychedelic ringleader who would become Bootsy’s spiritual partner in funk crime. Clinton absorbed the Collins brothers into Parliament-Funkadelic—the P-Funk collective that would soon rewrite Black music with a cosmic, unapologetically Black aesthetic. Bootsy’s bass became the heartbeat of albums like “Mothership Connection” (1975) and “Funkentelechy vs. the Placebo Syndrome” (1977), records that didn’t just make you dance but expanded the funk universe into a mythology of spaceships, clones, and freedom.

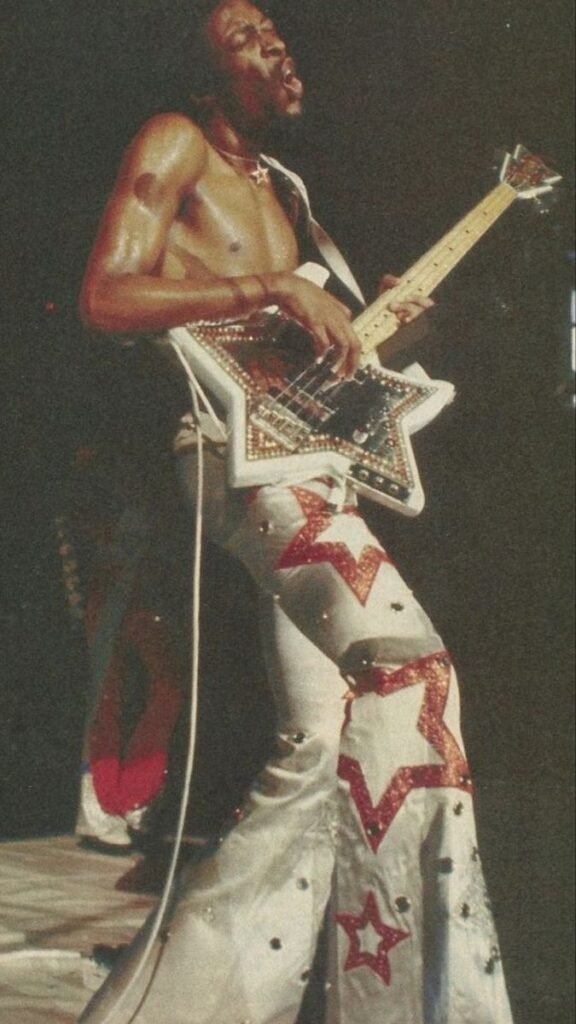

Tracks like “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof off the Sucker)” and “Flash Light” showcased Bootsy’s thundering yet playful style—fat bottom-heavy grooves, popping syncopations, and his signature wah-wah pedal that turned the bass into a conversation. What set him apart wasn’t just technical chops; it was the way he performed the bass as a character. With his star-shaped glasses, flamboyant costumes, and cosmic swagger, Bootsy wasn’t just a sideman—he was the face of the funk rebellion. By the late ’70s, Bootsy was a full-blown star, riding the crest of P-Funk’s success as they filled stadiums and kept the dance floors sweating.

By 1976, Bootsy was ready to orbit on his own. With George Clinton’s blessing, he launched Bootsy’s Rubber Band, a project that took funk’s party ethos and amplified it with Bootsy’s cartoonish, larger-than-life personality. Their debut, “Stretchin’ Out in Bootsy’s Rubber Band” (1976), was both funky and cheeky, setting the tone with hits like “I’d Rather Be with You”, a bass-driven ballad that became an underground anthem. Over the next few years, Bootsy released a string of Rubber Band albums—“Ahh…The Name Is Bootsy, Baby!” (1977) and “Bootsy? Player of the Year” (1978)—cementing his reputation as the clown prince of funk. His music was playful, sexy, and futuristic, but never shallow; it was liberation through rhythm. At the same time, Bootsy remained deeply collaborative, lending his bass wizardry to projects with Sly Stone, Bernie Worrell, and later crossing genres with the likes of Herbie Hancock and Deee-Lite (remember “Groove Is in the Heart” (1990)?). His studio in Cincinnati, Bootzilla Productions, became a hub for nurturing talent, showing that Bootsy wasn’t just about feeding his own stardom—he wanted to keep the funk ecosystem alive. Even after the commercial decline of funk in the ’80s, Bootsy kept reinventing himself, popping up in hip-hop, electronica, and beyond, his name carrying weight across generations.

So why does Bootsy Collins matter, not just in funk history but in the larger story of Black music? Because Bootsy is the architect of groove. He turned the bass—traditionally a background instrument—into the star of the show, giving it voice, character, and charisma. Without Bootsy, there’s no G-Funk in West Coast hip-hop, no Dr. Dre-era bass lines, no Snoop Dogg floating on that low-end cushion. Without Bootsy, electronic acts like Daft Punk and Flying Lotus wouldn’t have the same funky DNA in their beats. He embodied the philosophy that funk is more than music—it’s freedom, it’s community, it’s rebellion against rigidity. Bootsy taught us that the bass could be both the foundation and the fireworks. His legacy continues every time a bass player slaps a note with swagger, every time a DJ drops a P-Funk record at a party, every time a young artist decides to wear outrageous shades and claim their eccentricity. Bootsy once said, “Funk is making something out of nothing.” That’s exactly what he did: he took a teenage dream in Cincinnati, a stint with James Brown, a cosmic ride with George Clinton, and spun it all into a lifelong groove that still resonates. Bootsy isn’t just part of the funk story—he is the funk story, and he’s still stretching it out for anyone ready to dance.

The Ultimate Bootsy Collins Discography

1) With James Brown / The J.B.’s (Pacemakers era — 1970–1971)

Bootsy’s first official recordings came when he and his brother Catfish joined James Brown’s band, The J.B.’s. He was only 18, but he was already shaping the sound of the new funk.

• James Brown – Sex Machine (1970) — classic live/studio double, featuring Bootsy and The Pacemakers bringing raw new energy.

• James Brown – Super Bad (1971) — includes Bootsy-era bass lines on “Super Bad” and “Soul Power.”

• James Brown – There It Is (1972) — Bootsy still present in some cuts.

• James Brown – Love, Power, Peace: Live at the Olympia, Paris 1971 (recorded 1971, released later) — the definitive live document of the Collins brothers with Brown.

2) With George Clinton / Parliament-Funkadelic (mid to late ’70s)

Leaving Brown’s strict regime opened the door to George Clinton, and Bootsy jumped straight into the P-Funk mothership. His bass became the heartbeat of the movement.

• Parliament – Up for the Down Stroke (1974)

• Parliament – Chocolate City (1975)

• Parliament – Mothership Connection (1975) — cornerstone of the funk universe.

• Parliament – The Clones of Dr. Funkenstein (1976)

• Parliament – Funkentelechy vs. the Placebo Syndrome (1977) — includes “Flash Light,” with Bootsy’s synth-bass lines that defined a generation.

• Funkadelic – multiple albums, 1974–1979 — Bootsy appears throughout this golden era, weaving bass and vibe into Clinton’s psychedelic chaos.

3) Bootsy’s Rubber Band & Solo Career (1976 onwards)

By the mid-’70s, Bootsy was ready to orbit on his own, creating a body of work that still stands as pure funk gospel. Here’s the core studio discography:

• Stretchin’ Out in Bootsy’s Rubber Band (1976)

• Ahh… The Name Is Bootsy, Baby! (1977)

• Bootsy? Player of the Year (1978)

• This Boot Is Made for Fonk-N (1979)

• Ultra Wave (1980)

• Sweat Band (1980) — side project, but Bootsy-led through and through.

• The One Giveth, the Count Taketh Away (1982)

• What’s Bootsy Doin’? (1988)

• Jungle Bass (1990) — Bootsy’s Rubber Band return.

• Blasters of the Universe (1994, Bootsy’s New Rubber Band)

• Fresh Outta ’P’ University (1997)

• Play With Bootsy (2002)

• Christmas Is 4 Ever (2006)

• Tha Funk Capital of the World (2011)

• World Wide Funk (2017)

• Album of the Year #1 Funkateer (announced for 2025)

4) Iconic Singles & Collaborations

A discography this deep comes with more than just albums — Bootsy’s fingerprints are on countless singles and guest spots.

• “I’d Rather Be With You” (1976) — Bootsy’s signature ballad and an enduring funk anthem.

• “Flash Light” (Parliament, 1977) — Bootsy on synth bass, one of the most sampled tracks in hip-hop.

• “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof Off the Sucker)” (Parliament) — one of the great party anthems of the 20th century.

• Guest appearances with Herbie Hancock, Sly Stone, Deee-Lite (the unforgettable “Groove Is in the Heart”), and Bill Laswell’s Zillatron project (Lord of the Harvest, 1994).

5) Live, Compilations, and Rare Cuts

For the crate diggers, here’s where you’ll find more Bootsy magic outside the main albums.

• James Brown – Love, Power, Peace: Live at the Olympia, Paris 1971 — already mentioned, but worth stressing as a must-have.

• Best Of / Anthologies — multiple collections of Bootsy’s Rubber Band and solo work exist, from Warner Bros. to later reissues.

• P-Funk live recordings — Bootsy pops up throughout Parliament-Funkadelic’s expansive live archive.