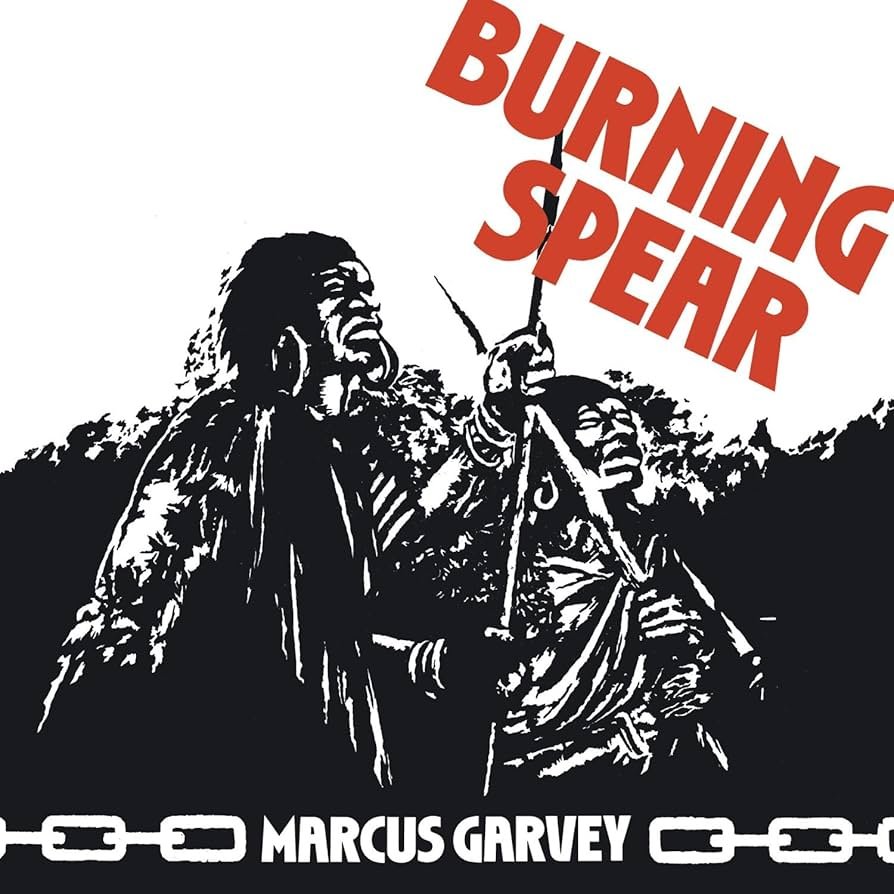

When Winston Rodney, better known as Burning Spear, released Marcus Garvey in 1975, Jamaica was standing at a cultural and political crossroads. Independence was little more than a decade old, yet the promise of self-determination was already clouded by economic hardship, class divisions, and political violence. Rastafari was rising from the margins into the mainstream, with reggae becoming its most powerful megaphone. Into that moment stepped Burning Spear, not with fiery militancy or Marley’s stadium-ready anthems, but with a voice that sounded ancient, solemn, almost priestly. His chants weren’t just songs — they were meditations, oral histories, spiritual teachings. And by invoking Marcus Garvey, the Pan-African prophet who urged Black people to look inward and return to Africa in spirit if not in body, Spear tethered reggae to a deep lineage of struggle, dignity, and resistance. Marcus Garvey wasn’t just an album; it was a ritual, a call to remember, and a soundtrack for survival.

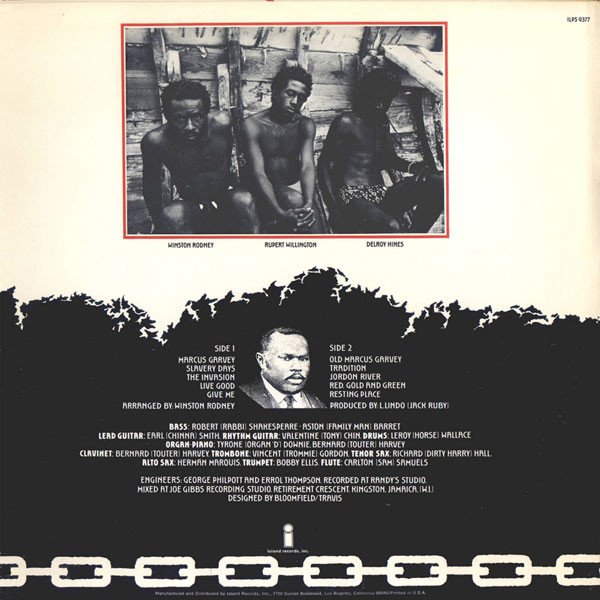

The production of Marcus Garvey was as striking as its message. Recorded at Randy’s Studio 17 in Kingston and produced by Jack Ruby, the album benefited from a sonic clarity and weight that gave Spear’s chants a cathedral-like presence. Ruby built a house band known as the Black Disciples, a collective of top-flight Jamaican musicians including Aston “Family Man” Barrett on bass (moonlighting from The Wailers), Robbie Shakespeare, Earl “Chinna” Smith on guitar, Tyrone Downie on keyboards, and a powerful horn section. Together they carved out rhythms that were steady and hypnotic, perfectly suited to Spear’s incantatory delivery. The drums and bass hit like ritual heartbeat, the horns cut through with prophetic urgency, and Spear’s harmonies with Rupert Willington and Delroy Hinds created a communal chorus — less lead-singer-and-backup than one unified chant. Island Records later remixed the album for international release, smoothing some of Ruby’s raw edges, but the original Jamaican pressing remains the truest vision: stark, heavy, unshakeable.

The power of the album lives in its essential tracks, each one a cornerstone of roots reggae. The title track, “Marcus Garvey,” sets the tone immediately — a rallying cry that reframes Garvey as a living presence, a prophet whose teachings still demanded attention. Over a pulsing bassline and stabbing horns, Spear doesn’t sing so much as proclaim, his words carrying the weight of scripture. Then there’s “Slavery Days,” perhaps the most devastating cut on the record. Spear’s simple, repeated question — “Do you remember the days of slavery?” — is delivered without ornament, without pity, just a sober reminder that history is not past but present. The repetition works like a mantra, refusing to let the listener look away.

“The Invasion” expands the scope, referencing foreign powers exploiting Jamaica and the Caribbean, tying local struggles to a global system of oppression. The groove is deceptively relaxed, but the message is sharp as a blade. “Old Marcus Garvey” looks at the way Garvey’s legacy was already being sanitized and neglected, with Spear insisting on keeping the fire of memory alive. It’s a reminder that history is never safe from distortion, and music can be the tool to correct the record. Meanwhile, “Live Good” strips the politics down to spiritual essence — urging moral clarity and community as the true foundation of liberation. Finally, “Tradition” closes with a warning and a plea: hold onto your roots, because without them, freedom is an illusion. These songs weren’t radio bait or party starters; they were lessons, offered in the form of hypnotic chants wrapped in heavy basslines.

Looking back, the impact of Marcus Garvey is hard to overstate. It marked Burning Spear as one of reggae’s great visionaries, distinct from Marley’s populism or Peter Tosh’s militancy. His music was slower, deeper, less about crossover appeal and more about communion. The album solidified the sound of “roots reggae” — not just in musical terms, but as a philosophy that tied Rasta spirituality, Pan-African politics, and Jamaican lived experience into one inseparable force. Its influence rippled outward: through reggae’s global expansion, into the dub experiments of the late ’70s, and forward into generations of artists who sought to make music not just as entertainment, but as testimony. You can hear its echoes in roots revivalists like Midnite, in the spiritual urgency of Sizzla’s early records, and even in hip-hop artists who framed their rhymes as cultural instruction.

So why, in 2025, should you still spin Marcus Garvey? Four reasons. First: because it captures reggae at its most uncompromisingly spiritual, unbent by commercial pressures. Second: because it’s a masterclass in minimalism — a few instruments, a voice, and a message, woven into something eternal. Third: because it connects you directly to Marcus Garvey’s legacy, reminding us that music is a vessel for history. And fourth: because once Spear’s voice enters your ears, solemn and unhurried, it’s impossible not to feel the gravity — the sense that you’re not just listening to a record, you’re participating in a ritual. Marcus Garvey isn’t background music; it’s a fire you sit beside, a reminder that the past is always with us, and that music, at its best, carries both memory and prophecy.

Tracklist — Marcus Garvey (1975)

1. Marcus Garvey – 3:27

2. Slavery Days – 3:34

3. The Invasion – 3:22

4. Live Good – 3:16

5. Give Me – 3:09

6. Old Marcus Garvey – 4:01

7. Tradition – 3:29

8. Jordan River – 3:17

9. Red, Gold & Green – 3:12

10. Resting Place – 3:12