By 1973, Herbie Hancock had already lived a few musical lifetimes. He’d been the young piano genius drafted into Miles Davis’ second great quintet, pushing post-bop into uncharted modal and free territories. He’d led his own adventurous groups, including the Mwandishi sextet, diving deep into spacey, avant-garde fusion that stretched jazz into cosmic abstraction. Yet as dazzling as those projects were, they weren’t reaching beyond the inner circle of jazz heads.

Meanwhile, the cultural climate was shifting: funk had become the heartbeat of Black America, with James Brown, Sly Stone, and Parliament-Funkadelic making grooves that spoke to dance floors and social movements alike. The civil rights era had bled into Black Power, and there was a hunger for music that was both complex and communal. Herbie, restless as ever, heard the call. With Head Hunters, he set aside the spacier edges of fusion and aimed straight for the gut — crafting a sound that fused jazz sophistication with funk’s raw, body-moving power. The result wasn’t just a pivot; it was a cultural earthquake.

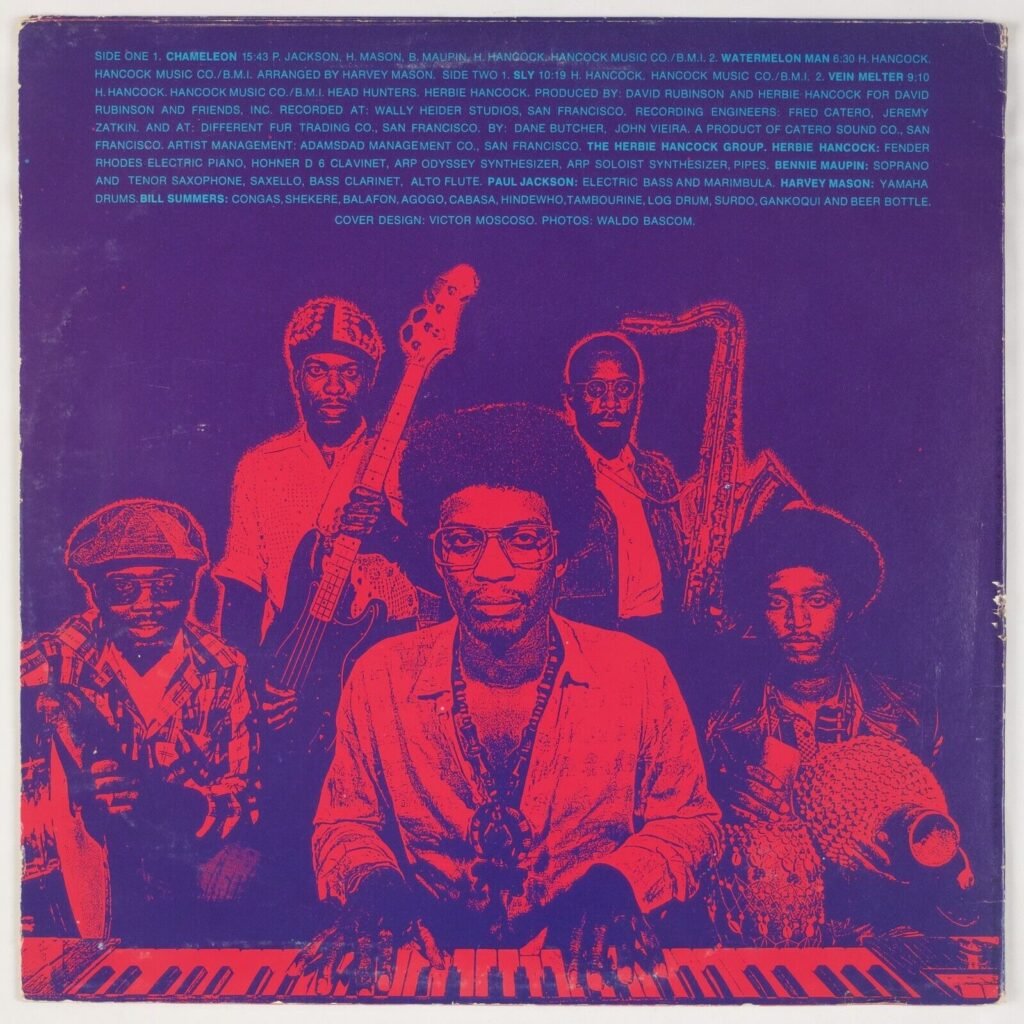

The making of Head Hunters was as intentional as it was experimental. Hancock assembled a leaner, funk-focused band compared to the sprawling Mwandishi lineup. Out went the horns and extra electronics; in came a stripped-down quartet-plus-percussion that would groove like a machine. Bennie Maupin, the only holdover from Mwandishi, handled sax, bass clarinet, and flute, adding a dark, textural counterweight to Herbie’s keyboards. Paul Jackson laid down bass lines that walked a fine line between jazz agility and funk heaviness.

Harvey Mason, one of the era’s most versatile drummers, locked in with Jackson to form the backbone, while percussionist Bill Summers gave the music its earthy, Afro-Caribbean pulse. Herbie himself commanded a fleet of keys — Fender Rhodes, ARP Odyssey, clavinet — layering futuristic tones over primal rhythms. The sessions, recorded at Wally Heider Studios in San Francisco, were both freewheeling and tightly conceived. Hancock’s vision was clear: create a jazz record that could speak the language of the streets without dumbing down the music. What emerged was a set of four tracks, each long enough to stretch, each tight enough to hook.

The album opens with “Chameleon,” a 15-minute funk odyssey built on one of the most iconic bass lines in history, played not on bass but on Herbie’s ARP synth. From the first squelch, it’s clear this isn’t jazz as usual — this is body music. Jackson’s bass soon joins in, Mason rides the groove, and Herbie shifts between clavinet riffs and Rhodes washes, building layer upon layer. It’s a track that moves like a living organism, constantly mutating but always anchored in that irresistible two-note hook. “Watermelon Man,” a reworking of Herbie’s own 1962 hit, takes the familiar and rebuilds it for the funk era. Summers’ opening beer-bottle whistle, inspired by Central African pygmy music, sets a ritualistic tone before the groove snaps in. The melody is instantly recognizable, but the treatment — dirtier, funkier, drenched in clavinet — makes it feel brand new. Side two dives deeper.

On the Bt side, “Sly,” a tribute to Sly Stone, is looser and more experimental, stretching out with Maupin’s reeds weaving through dense rhythmic layers; it’s the album’s nod to the freer impulses of fusion, but it still rides a funk pocket. Finally, “Vein Melter” closes things out in a slower, moodier register — a meditative comedown that showcases Hancock’s sensitivity as much as his innovation. While “Chameleon” and “Watermelon Man” carry the star power, it’s the balance of the four that makes the album a complete statement: danceable, listenable, and artistically daring.

The impact of Head Hunters was immediate and enduring. It became the best-selling jazz album of its time, breaking through to audiences who had never bought a jazz record before, and its grooves infiltrated everything from hip-hop samples to jam-band setlists. For musicians, it rewrote the rulebook: suddenly the electric keyboard and synthesizer weren’t just novelties but central voices; the rhythm section wasn’t just support but the star; and jazz could be both technically advanced and irresistibly funky. For listeners, it offered an entry point — a record that could sit next to Stevie Wonder or Sly Stone as easily as Miles or Coltrane.

Half a century later, its relevance hasn’t dimmed. You still hear “Chameleon” in clubs, “Watermelon Man” in high-school jazz bands, and the record’s DNA in modern genres from neo-soul to electronic beat music. If you need four reasons to spin it today: one, it’s the funkiest jazz record ever made; two, it’s a masterclass in groove and texture; three, it’s a historic bridge between jazz tradition and popular Black music; and four, it’s simply timeless — a record that makes you move, think, and feel all at once. Drop the needle and let it remind you that the head and the body don’t have to be at war — in Herbie’s world, they dance together.

Here’s the original track list for Herbie Hancock – Head Hunters (Columbia, 1973):

Side A

1.Chameleon – 15:41

2.Watermelon Man – 6:30

Side B

3. Sly – 10:18

4. Vein Melter – 9:10