Before Tony Allen became the rhythmic backbone of Afrobeat, he was a self-taught drummer navigating the vibrant Lagos music scene of the 1950s and early 1960s. Born in 1940 in Lagos, Nigeria, Allen grew up surrounded by a diverse sonic landscape, where traditional Yoruba music coexisted with jazz, highlife, and early forms of Western pop. His early musical influences were deeply rooted in the drumming traditions of Nigeria, particularly the polyrhythmic structures of Yoruba percussion, but he was also captivated by the jazz greats—Art Blakey, Max Roach, and Elvin Jones.

Allen’s first professional drumming experience came through the burgeoning Nigerian highlife scene, a genre that blended West African rhythms with jazz and Latin influences. He played in several bands, including those led by Victor Olaiya and Sir Victor Uwaifo, where he honed his ability to mix traditional drumming with the swing and syncopation of jazz. His unique approach to rhythm—combining the steady pulse of highlife with intricate, offbeat syncopations—was already setting him apart as a drummer of exceptional talent.

In 1964, Allen’s life took a pivotal turn when he met Fela Kuti, a jazz-obsessed musician and bandleader who was assembling a new group, Koola Lobitos. Allen auditioned for the band, and Fela, immediately recognising his talent, reportedly said, “How come you are the only guy in Nigeria who plays like this?” Their partnership would go on to define an entire genre.

As the 1960s progressed, Koola Lobitos evolved from a highlife-jazz band into something much more radical. Influenced by James Brown’s funk, Coltrane’s free jazz, and the political climate in Nigeria, Fela and Allen crafted a new sound—Afrobeat. While Fela was the ideological and compositional force behind the movement, it was Allen’s drumming that gave Afrobeat its heartbeat. He developed a complex yet danceable groove that fused jazz improvisation, highlife’s fluidity, and the deep, hypnotic repetition of traditional African rhythms. Unlike conventional drumming, which often follows a strict time-keeping role, Allen’s style was multi-layered—his left hand, right hand, and feet all working independently, creating a percussive conversation within itself.

Throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, Allen and Fela co-created some of Afrobeat’s most enduring anthems, including Water No Get Enemy, Zombie, Gentleman, and Shakara. Allen was more than just a drummer; he was Fela’s co-arranger, shaping the extended compositions and call-and-response structures that defined Afrobeat’s sound. His contributions were so vital that Fela once admitted, “Without Tony Allen, there would be no Afrobeat.”

Despite their musical synergy, tensions between Allen and Fela grew, particularly over financial disputes and creative differences. By 1979, Allen decided to leave Africa 70, citing exhaustion from Fela’s relentless demands and lack of proper recognition. This marked the beginning of his solo career, where he sought to explore Afrobeat beyond Fela’s political messaging.

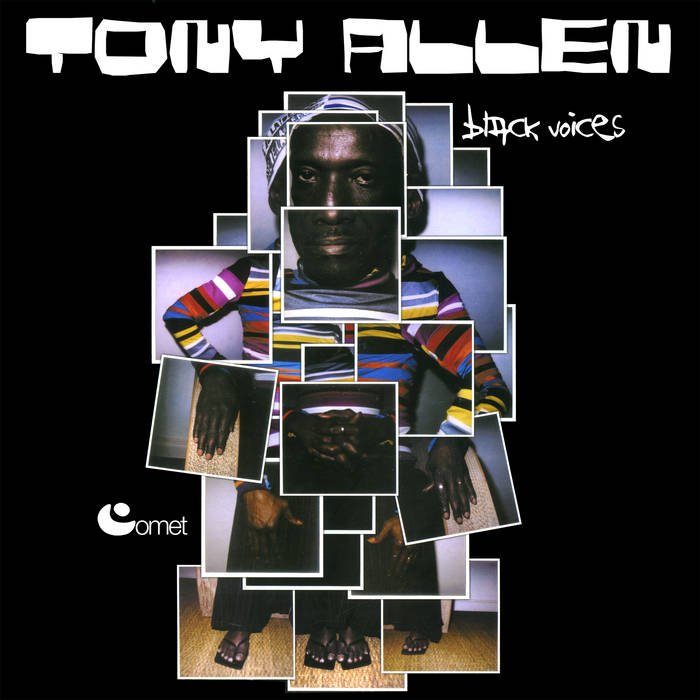

His first solo album, No Discrimination (1979), showcased his ability to take Afrobeat in new directions, blending it with jazz and funk while retaining the hypnotic grooves that made his drumming legendary. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Allen continued to experiment, releasing albums like N.E.P.A. (Never Expect Power Always) (1985) and Black Voices (1999), which infused electronic elements and dub into his signature rhythms.

During this period, he relocated to Europe, where he worked with a variety of artists across different genres, including French-African bands and jazz musicians. His collaborations with the likes of Ray Lema and Manu Dibango further expanded his musical horizons, cementing his reputation as a visionary percussionist who refused to be confined by genre.

The 2000s marked a renaissance for Tony Allen, as a new generation of musicians sought him out, eager to work with the man who had shaped Afrobeat. He collaborated with Damon Albarn on The Good, The Bad & The Queen (2007) and Rocket Juice & The Moon (2012), bringing his signature rhythms into the world of alternative rock and experimental music. His work with Albarn also opened the door to further global recognition, allowing him to bridge the gap between Afrobeat and contemporary music scenes.

Allen’s later solo albums, such as Secret Agent (2009) and Film of Life (2014), demonstrated his ability to innovate while staying true to his rhythmic roots. In 2017, he paid tribute to his jazz influences with The Source, a project deeply inspired by his early love of Art Blakey and bebop. His final album, There Is No End (2021), released posthumously, saw him working with a new generation of artists, blending Afrobeat with hip-hop and electronic music, proving that even in his final years, he remained as forward-thinking as ever.

Beyond his solo career, Allen’s collaborations with musicians like Flea (Red Hot Chili Peppers), Jeff Mills, and techno producer Moritz von Oswald demonstrated his versatility. He had a rare ability to fit his drumming into any context, whether it was jazz, rock, electronic, or traditional African music, all while retaining his unmistakable touch.

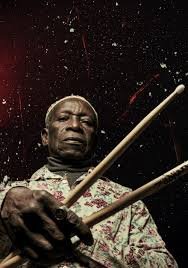

Tony Allen’s influence on music is immeasurable. He was not just Fela Kuti’s drummer; he was Afrobeat’s rhythmic architect, a musician whose technique and innovations reshaped global percussion. His unique drumming style—effortlessly fusing polyrhythms, syncopation, and improvisation—set a new standard for drummers worldwide. Unlike conventional drumming, which often relies on a steady backbeat, Allen’s approach was fluid, constantly shifting, yet always locking into a deep groove that anchored the music.

As a musician, he was a bridge between eras, from the golden age of highlife to the digital age of electronic beats. His legacy can be heard in countless artists who have drawn from Afrobeat, from Antibalas and Seun Kuti to electronic producers like Four Tet. His impact goes beyond genre; he was a drummer’s drummer, an artist’s artist—one of those rare figures whose influence ripples across generations.

When Tony Allen passed away in April 2020, the world lost a true pioneer. But his rhythm lives on. Every time an Afrobeat groove kicks in, whether in a Lagos nightclub, a European jazz festival, or a London studio, his spirit is there, keeping time, forever pushing music forward.

Here’s the full discography of Tony Allen with Fela Kuti, covering their work together from the 1960s to the late 1970s before Tony left Africa 70:

With Koola Lobitos (Pre-Afrobeat Era, Highlife-Jazz Phase)

1. Fela Kuti & His Koola Lobitos (1965)

2. Fela’s Special (1968)

With Africa 70 (Afrobeat Era, 1969–1979)

3. The ’69 Los Angeles Sessions (recorded in 1969, released later)

4. Fela Fela Fela (1970)

5. Fela’s London Scene (1971)

6. Why Black Man Dey Suffer (1971)

7. Shakara (1972)

8. Roforofo Fight (1972)

9. Afrodisiac (1973)

10. Gentleman (1973)

11. Confusion (1974)

12. Alagbon Close (1974)

13. He Miss Road (1975)

14. Expensive Shit (1975)

15. Everything Scatter (1975)

16. Kalakuta Show (1976)

17. Ikoyi Blindness (1976)

18. Upside Down (1976)

19. Yellow Fever (1976)

20. No Agreement (1977)

21. Stalemate (1977)

22. Johnny Just Drop (J.J.D.) (1977)

23. Sorrow Tears and Blood (1977)

24. Fear Not for Man (1977)

25. Opposite People (1977)

26. I.T.T. (International Thief Thief) (1979).

Here’s the full discography of Tony Allen’s solo career, covering his albums from the late 1970s until his passing in 2020.

Solo Albums

1. Jealousy (1975)

2. Progress (1977)

3. No Discrimination (1979)

4. Never Expect Power Always (N.E.P.A.) (1984)

5. Afrobeat Express (1984)

6. Secret Agent (2009)

7. Film of Life (2014)

8. The Source (2017)

9. There Is No End (2021, posthumous)

Collaborative Albums & Band Projects

• With Tony Allen & Afrobeat 2000

10. Live!! (1985)

11. Never Expect Power Always (1985)

12. Afrobeat Express (1992)

• With Ray Lema

13. Afro Jazz (1995)

• With Ernest Ranglin

14. In Search of the Lost Riddim (1998)

• With Doctor L

15. Black Voices (1999)

16. Psyco on da Bus (2001)

• With Jimi Tenor

17. Inspiration Information Vol. 4 (2009)

• With Damon Albarn & Flea (Rocket Juice & The Moon)

18. Rocket Juice & The Moon (2012)

• With Jeff Mills

19. Tomorrow Comes the Harvest (2018)

• With Hugh Masekela

20. Rejoice (2020, released posthumously)

EPs & Special Releases

• HomeCooking (2002)

• Lagos No Shaking (2006)