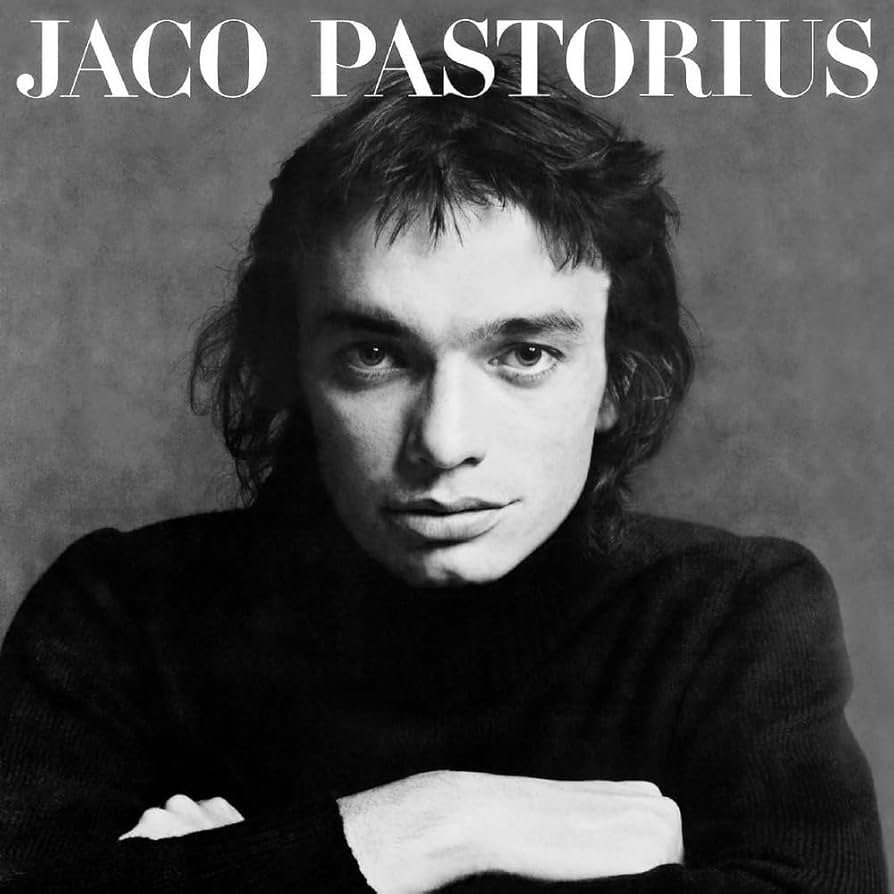

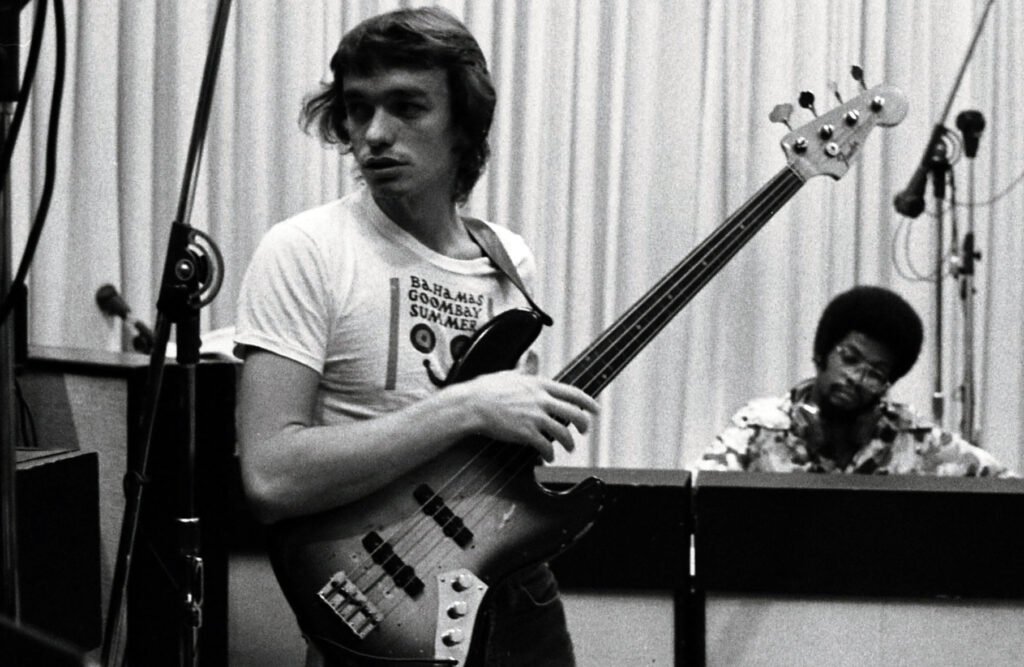

When Jaco Pastorius dropped his self-titled debut in 1976 he didn’t simply arrive — he insisted on a new grammar for the electric bass. Coming out of the stew of early-’70s jazz-fusion, funk and South Florida’s multicultural soundscape, this record landed at a moment when jazz was stretching toward rock, pop and world music and needed a player who could be both a melodic lead and a rhythmic engine. Jaco’s voice — the alto timbre of his fretless Fender, his uncanny harmonics and the way he treated the bass as a horn or a piano — felt like a cultural reset. It was an album made by a young man who grew up in gig bands, who absorbed Afro-Cuban percussion, R&B, big-band swing and the avant garde, then compressed all that into compositions that sounded modern and deeply human. More than technique, the record announced an attitude: bass could sing, lead, and compose entire landscapes.

The production and the roll call that made it plausible. Produced by Bobby Colomby (of Blood, Sweat & Tears) and cut in late 1975, the album is paradoxically intimate and lavish: small-group moments rub shoulders with horn charts, strings and star soloists. Jaco hand-picked a cast that reads like a who’s-who of fusion and jazz session players — Herbie Hancock on Rhodes and piano, Wayne Shorter on soprano, Michael and Randy Brecker, David Sanborn, Lenny White on drums, Don Alias on percussion, and even Sam & Dave stepping in for a gritty vocal on “Come On, Come Over.” That mix of elite jazz credibility and raw, streetwise charisma gave the record its edge: virtuosic players didn’t distract from Jaco’s vision, they amplified it. The sonics are clean but warm, the arrangements wide enough to let the bass breathe — and Jaco uses every inch of that space to reframe the bass from support to protagonist.

In terms of the tracking list, the album starts with “Donna Lee”, tackling the bebop warhorse is a statement in itself; Jaco turns the Charlie Parker (or Miles Davis) staple into a rapid, nervy bass/conga duet that announces both technique and taste. It’s flashy but tasteful: he can bop, he can swing, and he’s not afraid to let rhythm section colorations (Don Alias’ congas) recontextualize jazz tradition. “Come On, Come Over” then flips the record’s mood: Sam & Dave’s soul shouts over horn charts and Herbie’s clavinet, and Jaco locks a pocket that proves his sense of groove is as deep as his melodic daring. “Continuum” is where his lyrical side blooms — a less flashy, more songlike piece led by Rhodes lines and a patient drum feel, giving the fretless bass room to sing long, glassy notes and little moving countermelodies; here the instrument behaves like a human voice, and Jaco composes like a miniaturist, each phrase perfectly placed. These early tracks show his twofold intelligence: the ability to dazzle, and the taste to know when to be simple.

The album’s emotional center is twofold and quiet: “Portrait of Tracy” and the sprawling textures of “Opus Pocus.” “Portrait of Tracy” is a study in artificial harmonics that reads like a love letter — sparse, fragile and full of mystery; it’s one of those pieces that made generations of bassists stop and learn the physics of tone. Jaco uses harmonics almost like a harpist, creating chimey overtones that float above silence; the result is not a show-off trick but a hymn. Then “Opus Pocus” throws you back out into the ensemble: Wayne Shorter’s soprano, Herbie’s Rhodes and a layer of steel-pan shimmer from Othello Molineaux create an otherworldly fusion that folds Caribbean colors into hard jazz vocabulary. Both pieces show Jaco’s range: from soloist-poet to big-picture arranger who can orchestrate color, tension and release. The record’s sequencing — flash, groove, lyricism, orchestral sweep — makes it feel less like a debut and more like a fully realized statement.

So what did this album actually do to the bass, and why should anyone care now? For players it rewired possibilities: Jaco’s fretless tone, his use of mid-range punch, and his harmonics expanded the vocabulary of the electric bass forever. The story of his 1962 Fender “Bass of Doom” — the modified, essentially fretless instrument that became his signature voice — is part myth and part practical lesson in sonic invention: take what’s available and shape the sound you dream of. More broadly, this record taught musicians that the bass could be a melodic lead, a chordal instrument, an orchestra of textures and a composing tool in its own right; it influenced Weather Report, the neo-fusion movement, and a generation of players from Victor Bailey to modern session cats who use the instrument melodically. Decades on, the album still sounds immediate — its production holds up, the tunes remain beautiful, and the technical feats still surprise.

If you need four reasons to drop the needle tonight: one, it’s a masterclass in tone and phrasing for anyone who loves the instrument; two, it’s a rare debut that sounds like a finished artistic world; three, it marries virtuosity with real songwriting (not just chops); and four, it’s historically essential — an album that shifted how we listen to the low end. So whether you’re a bassist, a fan of fusion, or simply somebody who loves music that talks, sings and surprises, give this one a full playthrough: Jaco isn’t just playing his instrument — he’s inventing one.

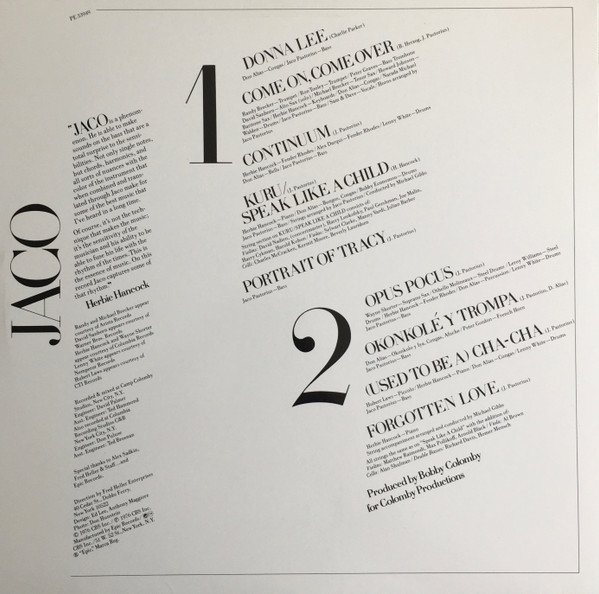

Track List Jaco Pastorius (1976, debut album):

1. Donna Lee

2. Come On, Come Over

3. Continuum

4. Kuru / Speak Like a Child

5. Portrait of Tracy

6. Opus Pocus

7. Okonkole Y Trompa

8. (Used to Be a) Cha-Cha

9. Forgotten Love