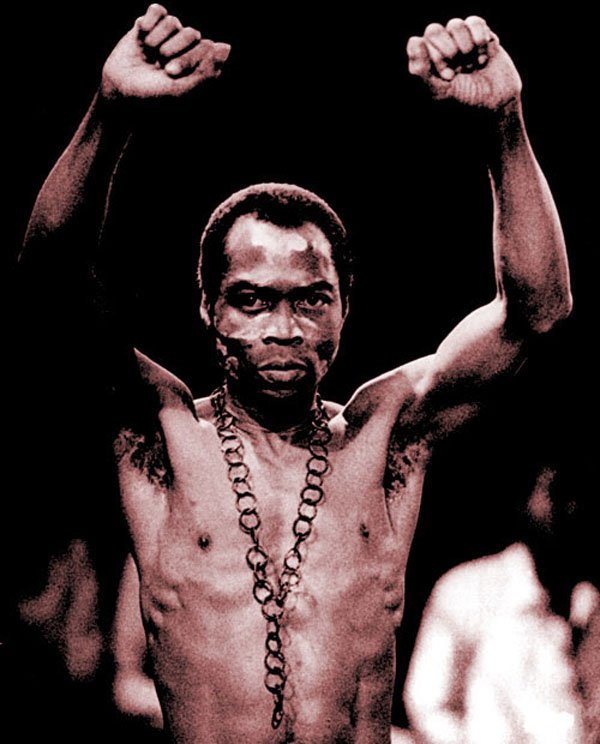

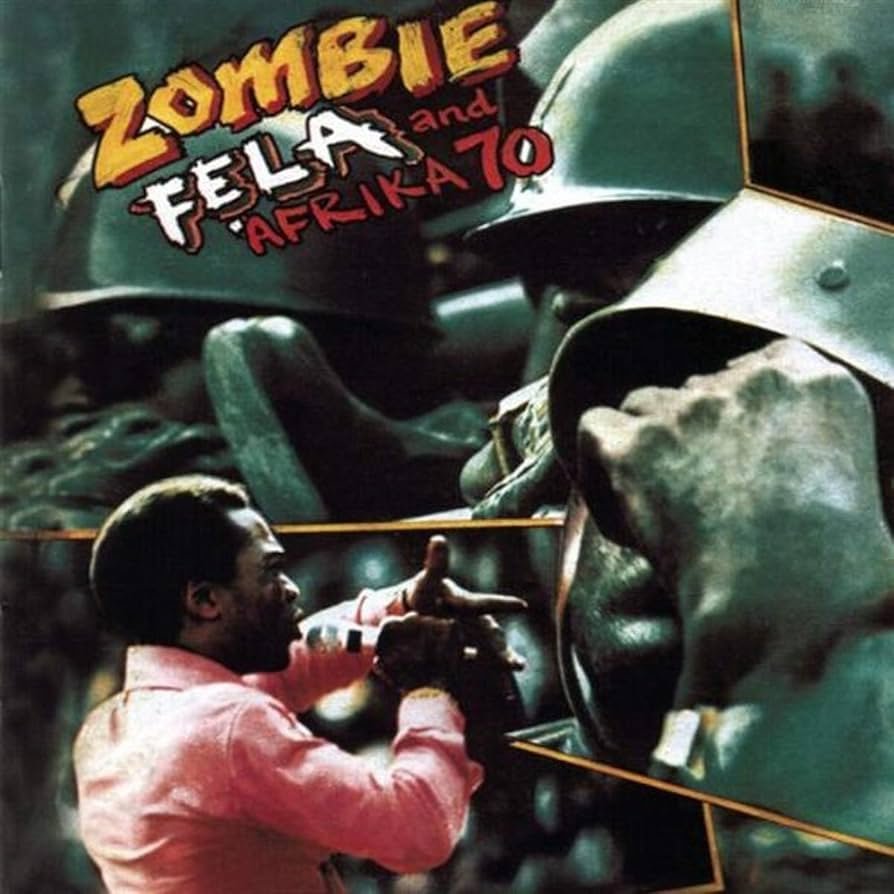

There are albums that arrive like quiet revolutions, whispered into a world that barely notices them. And then there is Zombie—a record that didn’t arrive so much as crash-land, fists raised, teeth bared, declaring war on a military machine that thought itself untouchable. When Fela Kuti and Africa 70 released Zombie in Nigeria in 1976, the country was deep inside a fever dream: the civil war had ended but its ghosts still stalked the streets, the military dictatorship was tightening its grip, and everyday Lagos swung between electric creativity and authoritarian dread. Fela had already positioned himself as a chronicler of this moment—equal parts shaman, bandleader, and political lightning rod—but Zombie is the exact point where those roles fused into something unstoppable. His influences were all colliding by then: the Yoruba spiritual lineage, jazz from Coltrane and Sanders, James Brown’s funk discipline, highlife’s cadence, and his own experimentations with extended Afrobeat architecture. Fela wasn’t just absorbing music; he was absorbing the rage and resilience of a people who were tired of being told to obey.

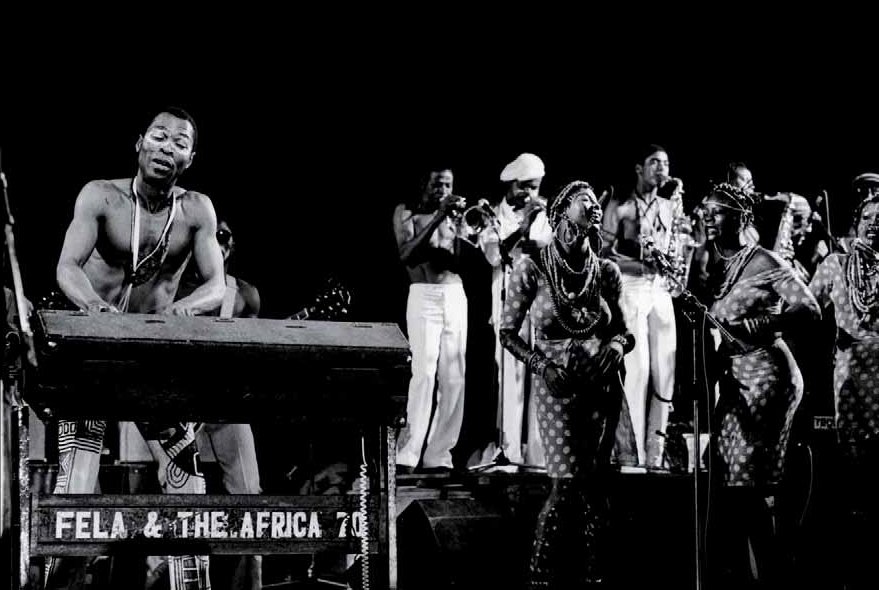

By the time he walked into the studio to record Zombie, he had already survived raids, arrests, and constant surveillance. His Kalakuta Republic—part commune, part spiritual center, part creative laboratory—was a thorn in the side of the Nigerian military. But that pressure didn’t intimidate him; it sharpened him. The sessions for Zombie were famously intense, built around the telepathic connection between Fela and drummer Tony Allen, the pulsating horn section, and the rhythmic discipline of Africa 70, who had become less a band and more a single organism with 40 lungs and one collective heartbeat. The recording took place between Lagos and the Decca studios that had become a sanctuary for radical music—every take stretching out into hypnotic, trance-like grooves. Fela led the band with an iron hand, but he also let them breathe, improvise, tease out rhythmic possibilities that most Western producers would have cut short. There were no guest stars. No flashy collaborations. Just a militant family of musicians with a shared mission: use music as confrontation.

Across its original two-track format, Zombie is a masterclass in how repetition becomes revelation. The title track opens with a marching-band mockery—horns snapping like drill sergeants, Allen’s drums locking the rhythm into a rigid, militaristic gait. Fela’s voice drops in with venom, using satire as a weapon: he calls soldiers “zombies,” mocking their blind obedience, their thoughtless violence, their role as extensions of authoritarian power. It’s not subtle, and it wasn’t meant to be. This was agit-funk—thick, fearless, and unashamedly confrontational. As the groove deepens, the whole band becomes an indictment. The call-and-response vocals echo street chants; the horns sound like a siren; the guitars chop through the mix like machetes in tall grass. At nearly thirteen minutes, “Zombie” is less a song and more an exorcism, pushing anger from the collective body of the Nigerian people into the open air.

The B-side track, “Mister Follow Follow,” offers a different shade of critique but is no less sharp. Here, Fela broadens his target: it’s not only soldiers who fall into blind loyalty, but ordinary citizens who choose complicity over courage. The groove is looser, almost deceptively mellow, but beneath it lies razorwire commentary. Fela warns of the dangers of following authority without questioning it, a message that remains painfully relevant decades later. Musically, this track highlights the elasticity of Africa 70—the horn lines sliding across the rhythm like warm oil, the guitars weaving intricate patterns, and Tony Allen drumming with a mathematician’s precision. The song builds slowly, like Lagos heat accumulating on asphalt, and then erupts into a hypnotic chant that lingers long after the needle lifts.

Taken together, the two tracks of Zombie form one of the most impactful political statements ever pressed to vinyl. They don’t just criticize; they illuminate. They don’t just soundtrack resistance; they become resistance. And as often happens when an artist speaks too much truth, the response was violent. Upon the album’s release, it spread quickly—not just across Nigeria but into Ghana, Benin, Senegal, and eventually into Europe and the U.S., especially through the 1977 and 1978 international re-releases. DJs in London and Paris treated Zombie like contraband scripture. Black American musicians, especially jazz and funk players, recognized a fellow traveler dismantling power structures with rhythm and fury. But Nigeria’s military government reacted with devastating force. In 1977, soldiers attacked Kalakuta, beat Fela nearly to death, and famously threw his mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti—a revolutionary icon—out of a window. She later died from her injuries. Fela responded the only way he knew how: with more music, more truth, and more defiance.

Decades later, Zombie stands not just as a cornerstone of Afrobeat but as one of the most courageous artistic acts in modern history. Its musicality is undeniable—the horn arrangements alone are enough to put it in the pantheon. But the album’s true power lies in its refusal to separate groove from struggle, rhythm from resistance. This is music with a backbone, a spine made of fire and iron. And though it was born in a specific Nigerian political moment, its relevance has stretched far beyond 1976 Lagos. Listen today and you’ll hear echoes in modern protest movements, in spoken-word resistance, in contemporary jazz, in the global funk underground, and even in hip-hop’s sharpest political cuts. Fela wasn’t just ahead of his time; he was building a future language for how music can challenge power.

For anyone approaching Zombie for the first time, or returning after years away, the album still demands your ears because it’s one of the purest expressions of Afrobeat’s architecture—uncompromising, extended, and intricately layered; it remains a blueprint for politically engaged music, showing how groove can carry critique without ever losing its pulse; the musicianship is staggering, especially Tony Allen’s drumming and the horn section’s tightrope precision; and it is a living historical document, a sonic snapshot of a people fighting for dignity in the face of oppression.

Zombie is not background music. It’s a boundary line. A manifesto. A warning flare. Drop the needle and it still feels dangerous—in the best possible way.

Tracklist — Fela Kuti: Zombie (1976)

1. Zombie

2. Mister Follow Follow